Have you ever felt like you’ve wasted hours of your life in meetings that weren’t very productive? What about the follow-up meeting(s) where everyone was supposed to do something, but didn’t, and then the meeting ends up going nowhere? There are tons of reasons why meetings go bad and the whole practice gets a bad rap. I’m not going to go into why meetings can suck since there is already plenty of content about that. I’d rather write about how a few friends and I applied cloud AI services to our project so it might inspire you to try them out on one of your projects. It’s a lot of fun and you can do amazing things.

There’s a lot of hype about AI and machine learning (ML) but there aren’t a lot of practical examples of how to use the various services available in real-world projects. I had wanted to use AI for a long time and even studied it a bit over the years, but never had a viable project to sink my teeth into until a few friends and I created Jetson—an interactive meeting note-taker and virtual assistant. When we started the project none of us were experts in either AI or ML, however, through it, we became familiar with methodologies, services, and libraries as well as met a lot of smart people who were (and still are) working on problems that haven’t been entirely solved yet—like identifying each person in a group by their voice and separating their speech into distinct channels.

As we worked on it the challenges expanded until we reached the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of speaker/voice separation, which, to my knowledge, still (3 years later as of this writing) hasn’t been fully overcome. It’s an interesting part of the story, but not integral to the main point—show a real-world example of how AI cloud services can be applied.

Hack Fact: Jetson started under another name—Meetbot. If you heard it rather than read it you might think we were making a meatloaf printer.

My friend Zaki and I worked together on another project at a company called Influitive and we often lamented how awful meetings could be. A year or so after we both left that company he reached out to me about a concept he had been tossing around with a few other people. It was pretty straightforward—make meetings better by transcribing what people said and provide a way for them to take notes on the transcription. I like building tools and it seemed like it could be really useful for a lot of people who experienced painful and unproductive meetings. Originally, the concept was simple but it quickly morphed into something more sophisticated—a meeting assistant capable of not only helping you take notes, but it would make suggestions, capture the next steps, and book future meetings. It evolved because we learned more about what services and libraries were available. After all, we had a better understanding of what we could do with them, and because of the amazing people who gave us feedback.

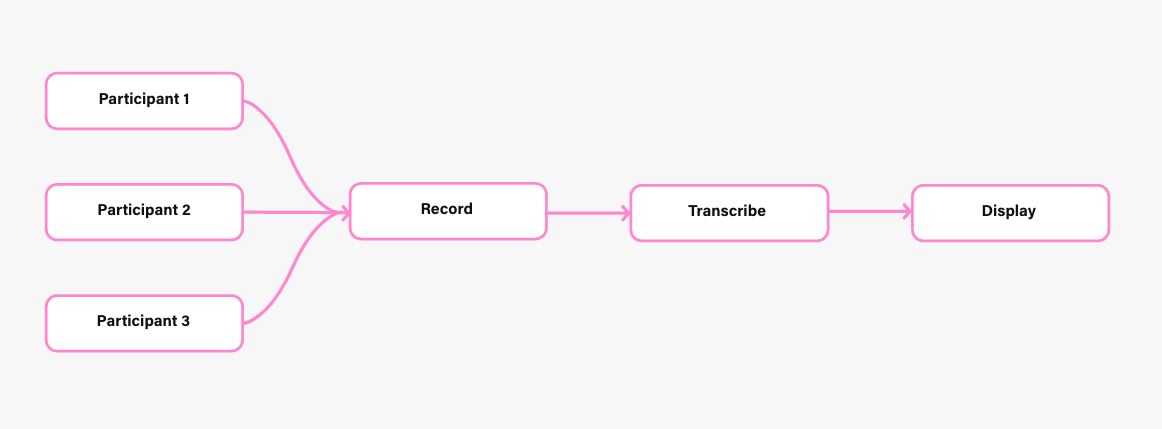

As with most new projects, the first thing we needed to do was figure out exactly what the biggest problem with meetings was. We felt like a lot of what makes meetings suck was time wasted trying to recap what agreements were made during the meeting. A.K.A. Action Items. Our first use case was, “A user wants to record action items and send them to the team after the meeting.” In other words, when an action item is spoken, the user should be able to add it to a list of all action items. Every time there was something actionable, you’d add it to the list. Simple, right?

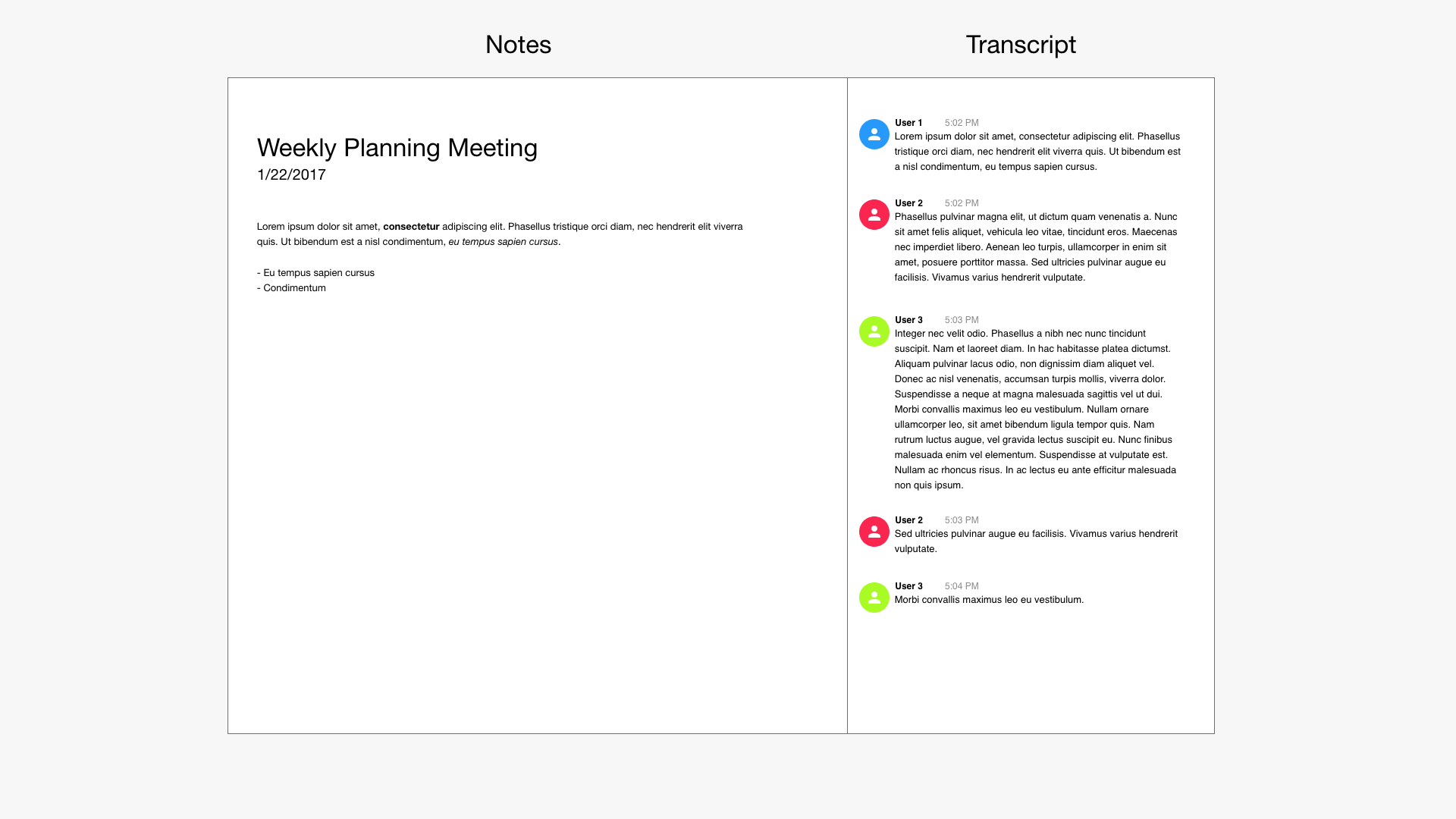

There were two main sections on the screen—Notes and Transcript.

Now that we had a solid use case it was time to figure out how to build it. We tossed around a lot of ideas and we landed on a visual UI that was split up into two sections; you could take notes on the left and read the transcript of the meeting on the right. The app would transcribe the meeting in near real-time and display the transcription on the screen in a Slack-like chat log, which you would use as a starting point for your notes.

Before we started building the UI we needed to make sure we could make the transcript. We hadn’t seen any examples of transcripts of multiple people in a meeting—at least not in a corporate setting, so we set out to do some research and found several options. We knew we’d likely need a piece of hardware with a microphone that sat in the middle of a conference table, but that was about it. As it turns out, separating voices from multiple speakers is enormously difficult. Dozens of really smart people have dedicated their entire careers to working on this one problem and, although a lot of progress has been made, it’s far from being considered solved.

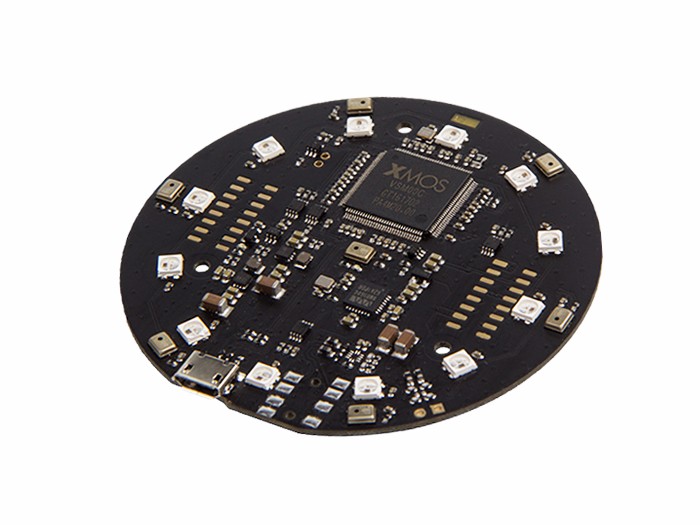

Naïvely, we thought were smart people and could sidestep the issue. We pretty much spent most of our time on it. Some of the options we mulled over were: giving participants lapel mics, setting mics at each position around the table, using array mics, and lastly, a pure software technique called speaker diarisation. The last item was the most alluring because it transcribed and identified the user at the same time; it was plug-and-play. The downside was that the best diarisation solution we found was proprietary and we had a really hard time getting access to test it out. After a megaton of research, alternately, we found a nice array microphone dev kit and considered it to be a good enough solution so we pursued it alongside third-party transcription and identification services.

For those who don’t know, an array microphone is an array of many tiny microphones spread out around a circuit board with some digital signal processing(DSP) capabilities meant to capture sound coming from 360 degrees around the board.

With modifications, we were able to reasonably separate voices in a room using the array microphone. We sent each person’s recording to Google’s Speech-to-Text cloud service but realized we couldn’t identify a user with it, so we had to find another service that did speaker recognition. Of course, speaker diarisation could handle both speech and speaker recognition at the same time, but we were still getting the runaround from the guy we met. Luckily, Microsoft had been developing their own AI/Cognitive services and they had a Speaker Recognition API available. The downsides were that you had to train it with each user’s voice so it could recognize you, and you had to send it to a speech recognition service for the transcript after identification. This additional step added some complexity to the app but it was our only viable option.

Ok, so we had separated source signals (voices) with our array mic board and had coherent chunks of speech audio being recorded and digitized—now we just needed to send this data to each service. Once we identified a participant, it was simple to transcribe their speech and tie it to their profile for display on the screen, however, at the time, most speech recognition services didn’t accept streaming audio. They expected one file per request and there was a time limit on the audio. Our job was to chop up the audio into coherent pieces so that the Speech Recognition service could effectively interpret it. For example, if you said, “Let’s work on the API early next week after we have had a chance to dial in the array mic.” You’d want to capture the entire sentence’s worth of audio so it made sense when transcribed. If you cut it off at “week” then the speech recognition service might interpret it differently like, “Let’s work on the API early next week. After we have had a chance to dial in the array mic, [next sentence].” This would be pretty bad in the context of a chat and would leave people wondering what was said. The partial solution to this problem was to try and detect when there was a pause long enough to indicate the end of a sentence and make a slice in the audio stream at that point. Luckily the DSP software on the board we chose had that capability baked in and you could set a threshold for how long the pause was. Of course, it wouldn’t work 100% of the time, but it worked well enough for us to test it out. There are edge cases where it doesn’t work, like in run-on sentences. We deliberately decided not to try and tackle edge cases at this point. Our efforts were dedicated to getting a working prototype and we knew there would still be some problems to address.

Once we had a good enough transcript, making it useful was the next challenge. Although there were a lot of really complex things going on under the hood, the user interface needed to be simple, yet very useful for us to feel comfortable with demoing it. We spoke with a lot of professionals who were in meetings every day and gathered feedback that led to some really interesting features being considered and developed. We knew we wanted to show a transcript of the meeting in a chat window, kind of like Slack, and we also wanted to have the ability to take notes on the transcript. How that shaped up is interesting and we had some help from a friend who was a UX researcher and designer at Evernote. The idea ended up being that you had a chat window on the right that was scrolling by as people were talking and on the left was a notepad. You could easily quote parts of the conversation by dragging it over from the chat window and use that as a starting point for notes. Anything in the note section was editable. We were able to mock this up fairly easily and get a working prototype but it felt like it was missing something.

Meeting notes are very useful, but wouldn’t it be more helpful if you could get suggestions based on what was being said in the meeting? For example, if someone says, “Ok, so I think the next steps are to make a list of all the features and draw up some wireframes”, then you could extract those steps and add them to the notes section. We learned a little bit about Natural Language Processing (NLP) from conversations we had with people who had worked on Alexa and Siri, so we knew it was the foundation for how those virtual assistants were able to understand what you were asking and formulate a response. Google had and has a great NLP service that you can train with your data to extract meaning from domain-specific information such as the next steps in a meeting.

NLP essentially reads a block of text and returns some keywords that help identify what the meaning is. You can train the NLP model to recognize domain-specific language like “next steps”, or “let’s meet next week”, or “action items”. Once you’ve interpreted the meaning you can then take some action like book another meeting.

We decided the best way to incorporate this feature was to introduce a chatbot that would make suggestions based on what was being said. If a participant starts talking about the next steps then the bot would jump into the transcript thread and ask if you wanted to make a next steps list. If you confirmed then a next steps list would populate in the notes. If you already had the next steps in your notes it would be added to them. If you were going to schedule a meeting, the flow would be a little more complex, the chatbot would pop up when it hears something about scheduling a meeting and asks if it should schedule. Upon confirmation, the bot would look up all participants, create a calendar invite for everyone, announce the meeting was booked in the transcript, and then add a note about it in the notes.

Once the meeting was wrapped up, the notes and transcript were saved in a meeting record that you could access from the Jetson dashboard. Every user would get a recap via email that also had a link to the meeting record.

Jetson ended up fizzling out but maybe you were able to learn something from our experience. There are a lot of ways you can use AI services and their APIs in your project and I feel like NLP or Natural Language Understanding is one of the most interesting because you can try to understand what people want to do based on what they said or wrote. There are a ton of ways you could apply that to your app. Sure, there’s a bit of a learning curve but you don’t need a Ph.D. in machine learning to use any of them. With some programming knowledge and experience, you could be up and running within a few days if not hours. Overall, we found Google’s APIs easiest to work with and had pretty good documentation. Microsoft seemed to return more accurate results but we didn’t run any experiments to verify that assertion.

I looked up some of the APIs we used while writing this article and it looks like speaker diarisation is in beta for Google’s Speech-To-Text service. It only handles up to 5 speakers at once, but even that would’ve been a game-changer for us. There are a lot more hardware options as well making it very tempting to pick it back up as a side project. It looks like Microsoft also has more NLP/NLU APIs available as well.